Special topics

Keeping track of changes

Hybrid occurrence tables

Keeping track of changes

The changes script records any edits made to Darwin Core data items. It lists the changes by record ID and field, and shows both the original data item and the edited one.

To use the script, first copy the Darwin Core table to be edited so that it's backed up. For example, an "event.txt" table might be copied to "event-old.txt", or "event-v1.txt" or "event-2024-10-06.txt". Next, make any needed edits to the original table. Run the script with the command

changes [original table] [edited table] [number of ID field]

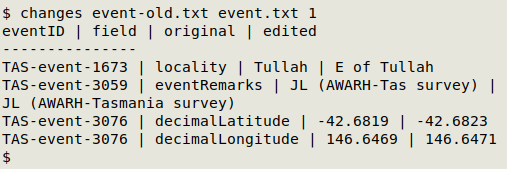

In the example below, I've made edits in several records in an events table. I copied the original table as "event-old.txt" before editing, and the table after editing was saved as "event.txt". The unique ID field eventID was field 1 in this table. Note that the two edits in eventID "TAS-event-3076" are shown separately.

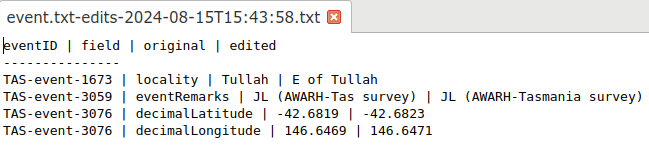

Besides displaying the changes in a terminal, the changes script also sends the report to a text file named for the edited table and a date/time stamp. In the example above, changes built the table "event.txt-edits-2024-08-15T15:43:58.txt" in the same directory as "event.txt". In a text editor, the changes table looks like this:

The changes script only shows edits within data items. If you are editing a table by adding, deleting or moving fields, or by adding, deleting or moving records, make these changes before doing data item edits and documenting them with changes.

Hybrid occurrence tables

Best practice with occurrence data is either to include all the event data items in each occurrence record, or to separate out the event data items in an event.txt table, and replace them in occurrence.txt with a corresponding eventID entry.

This doesn't always happen. Some Darwin Core datasets have both an event.txt table and an occurrence.txt table, with one or more event fields (such as eventDate) repeated in the occurrences table.

Are the repeated data items the same in both tables for the same eventID? There isn't an easy check to answer this question, but here I'll demonstrate one such check with a pair of fictitious data tables (below). In both tables there are the event data fields decimalLatitude, decimalLongitude, eventDate and recordedBy fields. To save space I've abbreviated some field names, e.g. "decLat".

event.txt:

| id | eventID | eventDate | decLat | decLon | recBy |

| bos1 | bos1 | 2025-03-16 | -24.7273 | 135.6194 | B. Tor |

| bos2 | bos2 | 2025-03-16 | -24.7268 | 135.6201 | B. Tor |

| bos3 | bos3 | 2025-03-17 | -24.9113 | 135.6128 | B. Tor | C. Ham |

| bos4 | bos4 | 2025-03-18 | -24.9106 | 135.6121 | B. Tor | C. Ham |

| bos5 | bos5 | 2025-03-19 | -24.9097 | 135.6099 | B. Tor | C. Ham |

occurrence.txt:

| id | occID | sciName | eventID | decLat | decLon | eventDate | recBy | indCount |

| pog001 | pog001 | Pogona vitticeps | bos1 | -24.7273 | 135.6194 | 2025-03-16 | B. Tor | 1 |

| pog002 | pog002 | Varanus giganteus | bos1 | -24.7273 | 135.6194 | 2025-03-16 | B. Tor | 1 |

| pog003 | pog003 | Pogona vitticeps | bos2 | -24.7268 | 135.6201 | 2025-03-16 | B. Tor | 2 |

| pog004 | pog004 | Varanus giganteus | bos2 | -24.7268 | 135.6201 | 2025-03-16 | B. Tor | 1 |

| pog005 | pog005 | Pogona vitticeps | bos3 | -24.9113 | 135.6128 | 2025-03-17 | B. Tor | C. Ham | 1 |

| pog006 | pog006 | Varanus giganteus | bos3 | -24.9113 | 135.6128 | 2025-03-17 | B. Tor | C. Ham | 1 |

| pog007 | pog007 | Suta suta | bos3 | -24.9113 | 135.6128 | 2025-03-17 | B. Tor | C. Ham | 3 |

| pog008 | pog008 | Pogona vitticeps | bos4 | -24.9106 | 135.6121 | 2025-03-18 | B. Tor | C. Ham | 2 |

| pog009 | pog009 | Varanus giganteus | bos4 | -24.9016 | 135.6121 | 2025-03-18 | B. Tor | C. Ham | 1 |

| pog010 | pog010 | Suta suta | bos4 | -24.9106 | 135.6121 | 2025-03-18 | B. Tor | C. Ham | 1 |

| pog011 | pog011 | Aspidites ramsayi | bos4 | -24.9106 | 135.6121 | 2025-03-18 | B. Tor | 1 |

| pog012 | pog012 | Varanus giganteus | bos5 | -24.9097 | 135.6099 | 2025-03-19 | B. Tor | C. Ham | 1 |

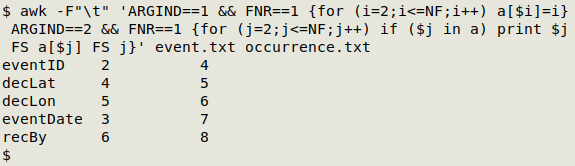

The first step in the check is to build a concordance that gives field numbers for the repeated fields (including eventID), first in event.txt, then in occurrence.txt. Note that I've excluded the id field (field 1), since if it's present it will presumably always be different between the two tables:

awk -F"\t" 'ARGIND==1 && FNR==1 {for (i=2;i<=NF;i++) a[$i]=i} ARGIND==2 && FNR==1 {for (j=2;j<=NF;j++) if ($j in a) print $j FS a[$j] FS j}' event.txt occurrence.txt

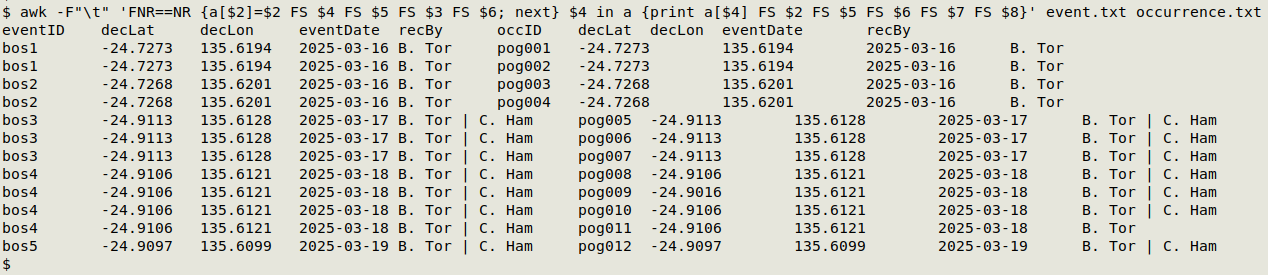

Step 2 is to build a tab-separated, combined events+occurences table with just the shared fields plus occurrenceID. Using AWK, this table-building has to be done using the concordance results, and since these can vary from dataset to dataset, the following command is "ad hoc" for my demonstration tables:

awk -F"\t" 'FNR==NR {a[$2]=$2 FS $4 FS $5 FS $3 FS $6; next} $4 in a {print a[$4] FS $2 FS $5 FS $6 FS $7 FS $8}' event.txt occurrence.txt

The third and final step is to work through the combined table and identify data items that differ for the same field and the same eventID. The AWK command that does this is again "ad hoc" because it depends on the placement of fields in the combined table. Since this third command works on the combined table, the step 2 and 3 commands are chained together. Again, I've abbreviated to save space:

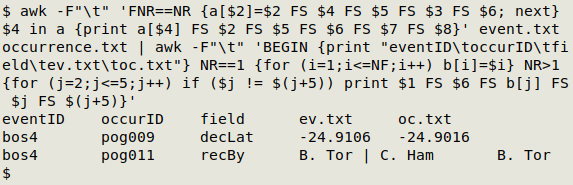

awk -F"\t" 'FNR==NR {a[$2]=$2 FS $4 FS $5 FS $3 FS $6; next} $4 in a {print a[$4] FS $2 FS $5 FS $6 FS $7 FS $8}' event.txt occurrence.txt | awk -F"\t" 'BEGIN {print "eventID\toccurID\tfield\tev.txt\toc.txt"} NR==1 {for (i=1;i<=NF;i++) b[i]=$i} NR>1 {for (j=2;j<=5;j++) if ($j != $(j+5)) print $1 FS $6 FS b[j] FS $j FS $(j+5)}'

This method successfully identifies the differing data items and reports their eventID, occurrenceID, fieldname and values in both event.txt and occurrence.txt. However, it's a very fiddly method and depends on careful attention to field numbers. There are probably better ways to do this with higher-level languages, such as Python.