For a full list of BASHing data blog posts, see the index page. ![]()

Data on clay

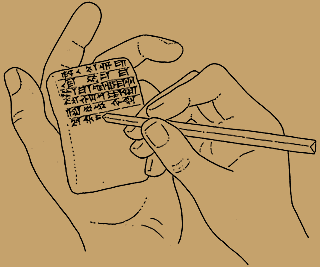

If you were wandering the streets of a busy city in the Fertile Crescent a few thousand years ago, you might have run across someone jotting down a few notes on a small clay tablet:

Image from mesopotamia.co.uk. Note the triangular cross-section of the reed stylus.

The jotting-down was done with the cut stem of a reed, and the result is today called cuneiform writing, after the wedge shape of some of the written elements (Latin cuneus, "wedge"). Cuneiform writing on clay was around for at least 3000 years and was adopted for use in a range of languages.

The advantages of writing-on-clay for data storage were obvious. It was cheap and simple, erasing was easy in the wet-clay stage, and a tablet would also accept carved-in or stamped-in images. If a tablet didn't need to be archived, its clay could easily be recycled by soaking in water. Dried-out waste documents could be used as building material.

The tablets with their cuneiform inscriptions were very durable if dried in the sun. Unlike writing on papyrus or leather, the writing on a clay tablet wasn't lost when the storage medium was exposed to fire, because clay doesn't burn — it just gets harder.

The biggest disadvantage of clay was also obvious. It's a bulky medium with a low data density per tablet, so the ideal use-case was storing small blocks of text.

The Dumb Cuneiform company will bake your tweet, SMS text or other short message, roughly transliterated into Old Persian cuneiform, for USD$20 per tablet.

Like many people, I'm fascinated by this ancient solution to the data storage problem. Archivists in the digital era have to cope with bit rot and frequent changes in media and format. Clay is clay, and today there are still hundreds of thousands of ancient cuneiform tablets, their data content unaltered after thousands of years.

If you're interested in cuneiform writing, you'll be pleased to hear that the major cuneiform symbol groups have been assigned blocks in Unicode. There are also online resources for everyday computer users who want to learn more about cuneiform and the cuneiform-using cultures. The Open Richly Annotated Cuneiform Corpus (ORACC) project not only welcomes new participants, but is also strong on FOSS and open data.

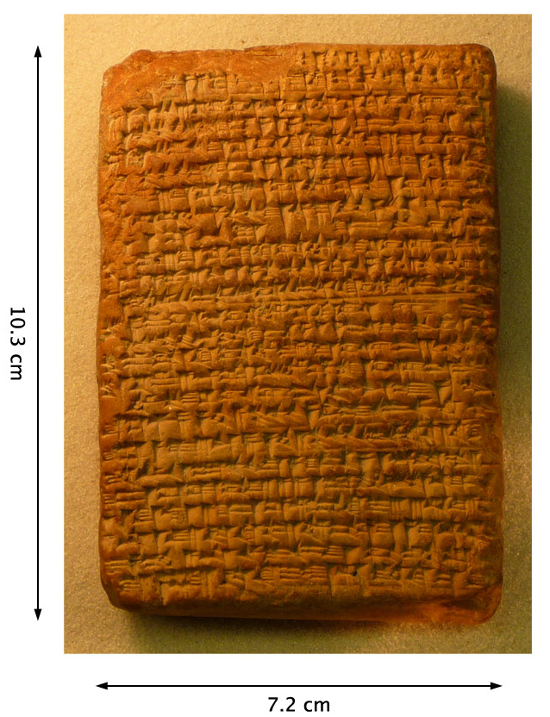

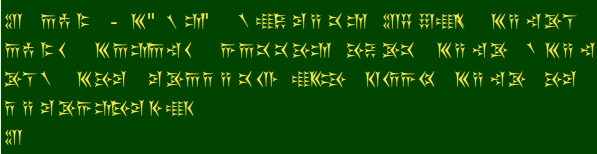

Image from the British Museum on the ORACC website. This tablet shows a contract of sale for a date orchard and is ca 2500 years old.

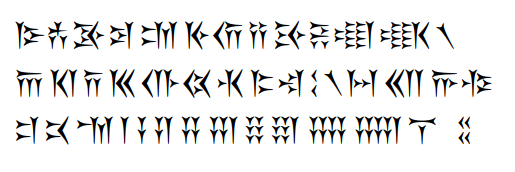

Some cuneiform TTF fonts are available. The best-looking I've found are the four Old Persian fonts built by "Fereydoun Rostam", the pseudonym of a Brazilian graphic artist: "Behistun", "Kakoulookiam", "Khosrau" and "Zarathustra". Fereydoun includes a keymap and a Unicode chart in each font package. All four fonts play well with LibreOffice:

and look great in a terminal:

Note that the Wikipedia article on Old Persian cuneiform says this partly alphabetic script was designed for use on hard surfaces, like monuments, rather than on clay tablets.

Last update: 2018-09-20

The blog posts on this website are licensed under a

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License